House prices in inner-ring suburbs in capital cities are poised to outperform this year, fuelled by wealthy home buyers and those who gained large amounts of equity during the pandemic boom, experts say.

Buyers who are receiving financial and practical support from families, an emerging force in those markets, could also drive prices higher.

Jarden chief economist Carlos Cacho said this pool of buyers would continue to dominate the housing market until interest rates fell.

“I think until we see rate cuts, the market will remain driven by higher-income or wealthy buyers,” he said.

“Given these buyers are generally concentrated in the inner-ring suburbs, it probably means those areas will continue to outperform.

“It also means we’re unlikely to see an improvement in new home purchase activity such as off-the-plan units or house and land – indeed HIA new home sales fell again in January and suggest downside risk for detached construction ahead.”

Mr Cacho said the surprisingly strong rebound in prices last year, when they rose more than 8 per cent, was largely powered by higher-income borrowers and those with larger deposits who were not constrained by credit.

“We can see this from CBA’s data showing the income of the average mortgage applicant has increased at twice the pace of the overall population, so the market is increasingly driven by high-income buyers,” he said.

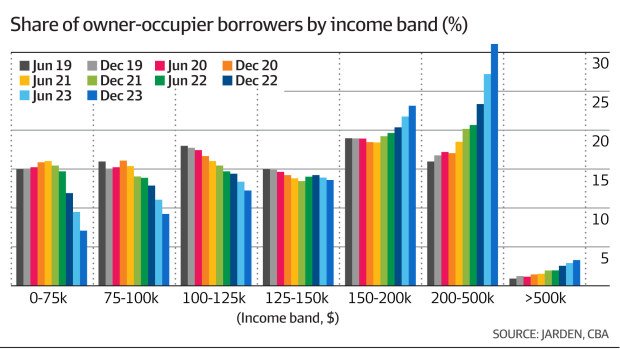

CBA’s half-yearly mortgage data shows the share of borrowers earning between $200,000 and $500,000 a year jumped to more than 30 per cent over the six months to December last year.

In contrast, the portion of mortgage applicants making between $75,000 and $100,000 a year lifted to only about 9 per cent during the same period.

Mr Cacho estimates that a household would need an income 50 per cent above the median to afford the average home. In Sydney, an income 80 per cent above median is now required.

This means borrowers would need to earn $148,560 a year to afford an average house nationally. Sydney buyers would need to earn $220,584 a year to afford an average house, and in Melbourne and Brisbane buyers would need about $153,000.

“Essentially, only the top 20 to 40 per cent of income earners across the capital cities can now comfortably afford an average home,” he said.

Couples better placed

Canstar finance expert Steve Mickenbecker said for single first home buyers, who were typically younger and probably on lower incomes, an average home would be out of reach.

“Couples are better placed to get their foot in the door,” he said. “For investors, the going is tough for those who still have a mortgage and are using the equity to buy for investment.

“The drain on servicing both loans is apparent and only upper-end income households in this position can participate.”

The affordability crunch is illustrated by the data from the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority which shows the proportion of new housing loans secured with a 20 per cent deposit or less shrank to 28.7 per cent in the September quarter last year, from 42 per cent in the December quarter of 2020.

Theo Chambers, chief executive of mortgage broking firm Shore Financial, said many buyers in the current market had gained large amounts of equity in the past three years, so they could put in bigger deposits and push prices higher.

“These buyers benefited from the pandemic housing boom so they are not concerned about their borrowing capacities being harmed by higher interest rates in the last two years because they have built up significant amounts of cash or equity,” he said.

Sally Tindall, director of research at comparison website RateCity, said that while the maximum amount households could borrow from the bank had been shredded by rising interest rates, people who were not planning to borrow at or near capacity may not have been affected by this.

“Data from CBA shows 89 per cent of new borrowers in the six months through to December 2023 still had spare borrowing capacity when taking out their loan,” she said.

Demographer Mark McCrindle of McCrindle Research said the financial and practical support that Baby Boomer parents or grandparents provided their children had enabled many aspiring home buyers to break into the housing market and had probably fuelled price increases.

“Baby Boomers, comprising 21 per cent of the population and owning 48 per cent of the national wealth, have a significant impact on the economic landscape through their wealth transfer to the younger generations,” he said.

“They’re not just helping their children but also their grandchildren directly by underwriting a mortgage or writing a private loan, or potentially going as tenants in common on property.

“In a lot of cases, the Boomers are helping their children or grandchildren break into the housing market by letting them stay in their home longer or by taking care of some of the other costs such as childcare to allow the children to save for a bigger deposit.”